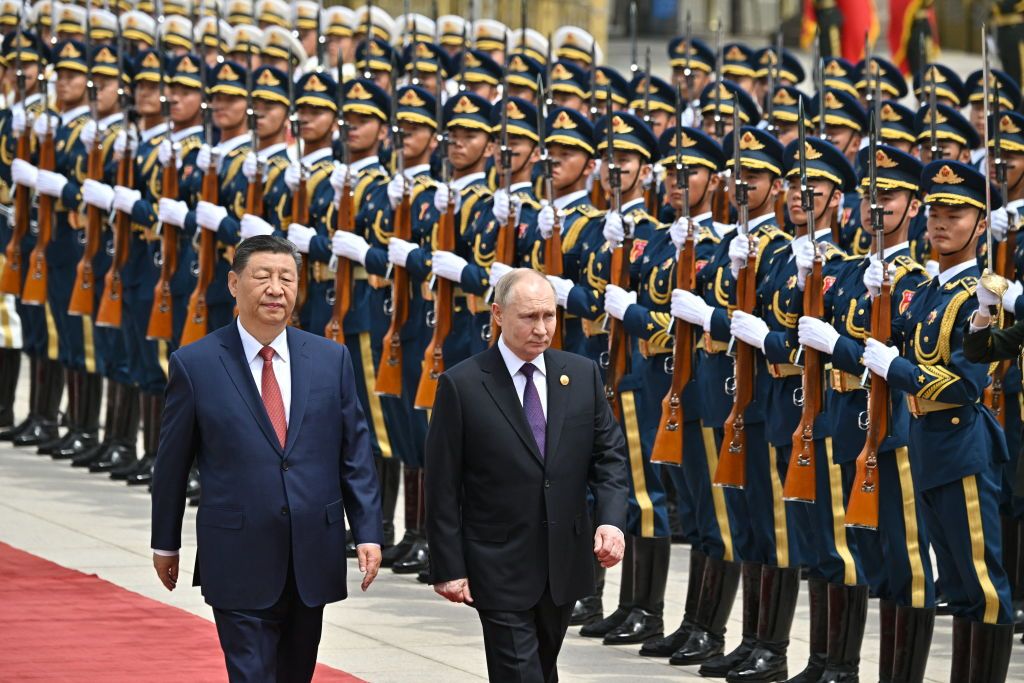

Last week, Russian President Vladimir Putin sent a clear signal to the West that China firmly supports Russia. President Putin visited Beijing on May 16 for the first time since his inauguration to meet with President Xi Jinping. The trip followed a cabinet reshuffle in Russia the previous week, the most important move being the appointment of Russian economist Andrei Belousov to replace Sergei Shoigu. Minister of Defense.

Belosov’s appointment suggests that President Putin now believes that the outcome of the war against Ukraine will depend on which side can mobilize the most resources in a long-term economic struggle. President Putin’s visit to Beijing suggests that he is preparing external elements with economic support from China.

Putin has a point in thinking that Russia’s war with Ukraine will depend on which side can outspend the other. At face value, one might think that Russia stands little chance, given its $1.8 trillion GDP compared to just over $40 trillion for Western countries. Add in China’s $17 trillion superpower economy, and the economic balance starts to look a little different.

Unfortunately, the West does not seem to understand that the focus of the war is on the economy and resources. Data shows that Ukraine lacks funds and resources. Annual Western aid to Ukraine, about $100 billion a year, is enough for Kiev to hold the line, but not enough to push Russia back (as evidenced by actions in recent weeks in Ukraine’s Donetsk and Kharkov regions). ing).

Counterattack: Cutting-edge Ukrainian fashion beyond Vyshyvanka

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in the twice-weekly newsletter “Fighting Back with Tim Mack” on May 20, 2024 and is republished with permission by the Kiev Independent. Ta. Click here to subscribe to Fight Back. When Russia’s all-out war against Ukraine began…

And with U.S. aid delayed by Congress, Western aid to Ukraine has waxed and waned. It peaked at about $8.5 billion in the first half of 2023, coinciding with Ukraine’s much-publicized fight back, but then dropped to just $3.7 billion per month between October 2023 and February 2024. This decline in Western funds came in tandem with Ukraine’s fight back, and its defensive struggle against Russia. No surprise there.

Western funding for Ukraine is inadequate, poorly coordinated, and lacks long-term planning and strategy. It’s ad hoc IV nutrition. There is no comprehensive long-term financing strategy in place for Ukraine, especially one that envisions a scenario in which Donald Trump wins the U.S. presidential election. President Putin, by contrast, has sought to provide Russia with a vision for long-term war resources. Sadly, the West doesn’t really understand what’s at stake here.

Fortunately, China’s support for Russia is far from heartfelt. Russia is dependent on Iran and North Korea, as China provides no direct military support and only limited equipment and ammunition. Why isn’t China fully engaged?

Essentially, China is not keen on undermining its exceptional global relationship with the United States, nor is it keen on escalating a trade war, and is mindful of avoiding harsh Western sanctions. So while Moscow may see China as a major international trading partner, that sentiment is not really reciprocated by Beijing. Russia is certainly beneficial to China, but for now it is just a minor player.

Rather, China is trying to draw a line between Russia and the United States. Wherever possible, Beijing is taking advantage of Russia’s weakening and growing dependency to buy discounted Russian goods diverted from traditional markets for Russia in Europe and to increase sales of non-military goods. Exports to Russia are made at the highest dollar rate, that is, the renminbi. As a result, bilateral trade between China and Russia is expected to grow by about a quarter in 2023 to a record $240 billion, tipping the balance in China’s favor.

Western countries have been nervous about the growth of this trade, particularly China’s increased exports of dual-use technologies to Russia, but China has been careful not to further jeopardize its relations with its main Western trading partners, and the threat of secondary sanctions against Chinese companies is now showing signs of moderating this trade, with Chinese exports to Russia declining year-over-year in March and April 2024.

President Xi Jinping’s visit to Europe last week reminded Europe that Russia’s war against Ukraine is a direct threat to European security. It also reminded China that if it wants to win over European allies in the U.S.-China trade war, it needs to carefully manage its relationship with Russia to avoid turning Europe toward Washington.

It is also important to recognize that there are stress points in China-Russia relations. First, tensions and border disputes remain in eastern Russia. This week’s Xi-Putin meeting appeared to acknowledge the situation with a new agreement, but tensions remain serious. Many Russians see China as Russia’s greatest long-term security threat.

Second, China’s decision not to provide arms to Russia has forced Moscow to turn its attention to North Korea, while China has become increasingly nervous and irritated by the deepening ties in its backyard. China is concerned about deepening cooperation between Russia and North Korea to further strengthen North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic weapons programs in return for North Korea supplying military supplies to Russia. A more militarily powerful North Korea that is less dependent on China is not in Beijing’s interest.

Opinion: Ukrainian Navy drones control the Black Sea

Russian forces have encountered a new enemy in the Black Sea: Ukraine’s naval suicide bomb arsenal. These seemingly small unmanned vehicles have been targeting Russia’s Black Sea Fleet since September 2022, picking off Russian battleships one by one. The latest in Ukraine’s maritime conquests…

Third, through its invasion of Ukraine, Russia is demonstrating that it is a global disruptor, a literal looser that wants to change the global status quo and is willing to take rash actions that risk upsetting global markets.In contrast, China has long valued what it has considered an inevitable accent on the rules-based international order that gave us globalization, free markets, and trade, and its global economic hegemony over the United States.

It is also noteworthy that China appears to have certain guardrails in place for Russian actions in Ukraine, making it clear that it does not support the use of nuclear weapons, for example, as outlined in China’s 12-point peace plan for a Russian war against Ukraine. However, China, which would have been initially surprised by the outbreak of all-out war, seems comfortable with a prolonged conflict as long as Russia maintains the guardrails.

A prolonged war would ultimately weaken Russia and make it more dependent on China, allowing China to buy cheaper goods and charge higher dollars for major exports to Russia. Russia’s struggles in Ukraine highlight that it may not have been clear in 2022 whether Russia was a junior partner in Sino-Russian relations (at least to President Putin).

China supports weakening Russia, but not defeating it. So Mr. Xi granted Mr. Putin the visit he wanted, and both signaled different points to the elephant in the room: Washington. President Putin has indicated that Russia is preparing for a long economic struggle for Ukraine. Mr. Xi suggested that if the United States wants to avoid a bad outcome on the Ukraine issue, China needs to act aggressively and limit its aid to Russia, in exchange for concessions on issues such as trade. He suggested that there was.

Editor’s note: The opinions expressed in the editorial section are those of the author and do not reflect the views of Kyiv Independent.

timothy ash

Associate Fellow at Chatham House