India’s lower house of parliament now has just 24 Muslim members, the second lowest number since independence. The number hit an all-time low of 22 in 2014, when the Indian National Congress, the biggest beneficiary of the Muslim vote, faltered in the electoral process. It then rose slightly to 26 in 2019, before falling again.

The BJP and other opposition parties have acted as guardians of Muslim interests and benefited from their votes. As a result, Muslim representation was directly tied to the prospects of these parties. This time, the BJP almost doubled its seats in the Lok Sabha from 52 to 99, while the BJP secured 234 seats, but Muslim representation did not increase accordingly; instead, it plummeted. This decline was not because Muslims did not vote for these parties, but because these parties, which ate into Muslim votes, avoided proportional allocation.

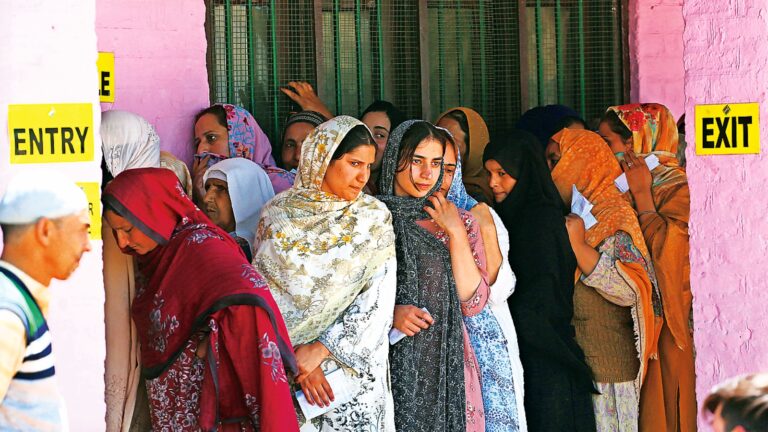

The BJP fielded just one Muslim candidate from Malappuram in Kerala. But the Muslim vote bastions – Indian National Congress, TMC, SP, NCP, RJD and Communist Party – fielded just 78 Muslim candidates against 115 in 2019. The Indian National Congress, known for its appeasement policies, fielded just 19 Muslim candidates this time against 36 in 2019. Other parties were similar, with the TMC giving just six seats to Muslims this time against 13 in 2019. The SP, the biggest beneficiary of Muslim votes in Uttar Pradesh, also reduced its number from eight to four seats. The result? The representation of the community, which constitutes 14% of the population (2011 census), fell to 4.4% in the 18th Indian Lok Sabha. The community does not have a single representative from states like Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Odisha and many others.

This is hardly a happy situation for the Muslim community. Some political commentators blame the BJP for creating this environment of decline. This is tantamount to slandering the Indian electorate, which elected 21 Muslim MPs to Parliament in 1952, at the height of post-Partition sectarian violence. Four more Muslim MPs were nominated to the Lok Sabha, taking the number to 25.

Some Muslim leaders, such as Asaduddin Owaisi, lament the decision of Indian Muslim leaders not to form an all-India Muslim party like Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Muslim League after the partition of India. There is one remnant of the Muslim League in Kerala, which won three seats this time, but like Owaisi’s AIMIM, it remains a regional organisation. Leaders like Owaisi continue to embrace Jinnah’s ideas even 70 years after the partition of India.

Either assertion to blame the BJP or to aspire for a national political organisation for Muslims shows the inability of the community’s leaders to understand the real cause of their woes. The 2024 Lok Sabha elections is the latest manifestation of the fact that the Muslim community is stuck in polarised politics. The politics of defeating the BJP, which critics call “strategic voting”, serves the community’s vote merchants but not the community itself.

In competitive politics, polarisation on one side always leads to polarisation on the other. Such anti-polarisation in India is harmful to the Muslim community. Instead, we should work towards a politics of development and social change. The community is not monolithic. Around 95% of the community are Ajrafs and Arzars and the remaining 5% are Ashrafs. The Ashrafs consider themselves the descendants of early Muslim immigrants to India while the Ajrafs and Arzars are those who converted to Hinduism from the OBC and Dalit communities. Together they are called ‘Pasmandas’ (those left behind) in Persian.

The BJP preferred to champion Pasmanda development and social concerns, namely caste discrimination, economic and educational backwardness. At the party’s national executive meeting in Hyderabad in 2022, Prime Minister Narendra Modi encouraged party leaders to reach out to Pasmanda Muslims and met several times with prominent Pasmanda leaders. In the December 2022 state assembly elections in Delhi, the BJP fielded four Pasmanda candidates. In Uttar Pradesh, a Pasmanda Muslim serves as the Minister for Minority Welfare. In a by-election in the state last year, a Pasmanda candidate fielded by BJP ally Apna Dal won by a landslide over a Hindu candidate from the SP. In the run-up to the general elections, the BJP continued to reach out to the Pasmandas, recruiting “Modi Mitras,” or friends of Modi.

These efforts to wean the Muslim community away from ghetto politics initially seemed to be paying off. A study conducted by the US-based Carnegie Endowment earlier this year concluded that at the time of the 2017 Uttar Pradesh Assembly elections, 12.6% of general Muslims and 8% of Pasmanda Muslims supported the BJP. At the time of the 2022 state assembly elections, Pasmanda support for the BJP had risen to 9.1%.

Unfortunately, the recent assembly elections have once again proved that the BJP’s efforts to de-sectarianise Muslim politics have not made much headway. The abandonment of its welfarist proposals has really hurt the interests of the Muslim community. This calls for serious introspection.

The author is the chairman of the India Foundation and is affiliated to the RSS.