In the ongoing 2024 general elections, more than 8,000 candidates are competing for 543 seats in the Lok Sabha. Many of these individuals are contesting for the first time.

One cornerstone of India’s electoral politics is the high turnover of elected representatives. Contrary to common practice in most democracies, incumbent candidates in India do not benefit from incumbency advantage; in fact, scholars have long spoken of an “incumbency disadvantage” in the Indian context.

In 2019, 226 elected members of Parliament (MPs) were incumbents (41%), which is a low figure considering that the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) consolidated the single-party majority it won in 2014. Only half of the BJP’s MPs (154 out of 303, to be exact) were elected in 2014, and 139 of its 149 non-incumbent MPs were elected to Parliament for the first time. Among the 228 elected Opposition MPs, only 67 were incumbents, while 132 were first-time MPs. Additional historical data on individual incumbency indicates that this phenomenon is not new. In fact, the share of reelected incumbent MPs was even lower during the first two decades after independence, during the previous era of the Congress’s dominance.

The turnover among India’s political class and the declining pool of stable political representatives raises important questions about the nature of representation in India and the functioning of legislative accountability. This article reviews six decades of data on candidates, nomination patterns, and incumbency to extract broader trends that will not only determine the contours of the 2024 race but also inevitably shape the new Parliament that is formed after June 4.

Dissecting political turnover

What explains India’s high rates of political turnover? The following sections utilise data from the Trivedi Centre for Political Data’s Indian Individual Incumbency Dataset, in which a unique identification number was coded for each of the 90,583 candidates who contested general elections in India from 1962 to 2019. This identification number enables the calculation of individual incumbency and career trajectory variables, such as the number of elections contested, terms served, incumbency status, as well as turncoat status of candidates.

The first explanation for the high turnover is that not all incumbent MPs rerun in the first place. From 1967 to 2019, fewer than 70% of all MPs, on average, re ran, and 55% of these re-running MPs got reelected. Therefore, if one does not factor in re-running rates, the average share of incumbent MPs in the Lok Sabha would stand at a scant 38%.

These figures are relatively consistent over time. The share of re-running MPs tends to increase when general elections are held in close proximity, as in the 1990s when a series of fractious coalition governments failed to complete their full five-year terms in office. In recent years, the share of rerunning MPs has declined further. In 2019, only 67% of all incumbent MPs stood for reelection.

The rate of incumbency varies across parties. For example, the Congress tends to retain more of its incumbents than the BJP. On the other hand, the renomination strategies of regional parties tend to fluctuate. In 2014, the ratio of rerunning incumbents was similar across the two national parties and regional parties. In 2019, by contrast, regional parties discarded most of their sitting MPs.

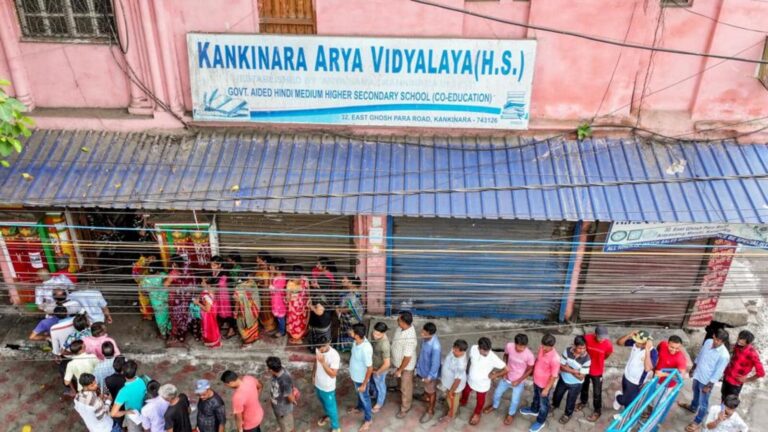

There are also regional variations. Some of the largest states —including Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal—exhibit a high rate of re-running incumbents. However, smaller states such as Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, and Telangana saw very few sitting MPs re-running in 2019. None of Chhattisgarh’s eleven MPs elected in 2019 were incumbents (and 10 of them were first-time MPs).

Candidate reshuffling is not a function of electoral competitiveness but of political parties’ distinct organisations, cultures, electoral strategies, and recruitment practices. For instance, the BJP in Gujarat — during Narendra Modi’s chief ministerial tenure — used to, on average, discard 50% of their members of the legislative assembly (MLAs) each election.

Over the last two decades, my research has shown that most political parties tend to recruit candidates from similar sociological pools made of self-funded individuals connected to local business networks. Therefore, it is easier to discard sitting MPs when they are recruited from outside party organisations. The Bahujan Samaj Party, which recruits its candidates from locally dominant social groups, is a case in point. Turncoats regularly fielded by parties also reinforce the notion that candidates are interchangeable.

An assembly of newcomers

As a result of this high turnover, three-quarters of all MPs elected since 1977 have been either first-time or two-term MPs. While a high turnover of representatives may indicate elite circulation, it also limits cumulative legislative experience among parliamentary representatives. In the 17th Lok Sabha, elected in 2019, only 22% of MPs were elected for a third term or higher and were well distributed across parties and across regions.

During Modi’s tenure as prime minister, the share of experienced MPs has significantly decreased to levels not seen since the 1970s. This modern-day decrease is unsurprising given that the BJP won many new seats with new candidates over the past two elections. In the case of the Congress, only eleven of the 52 MPs elected in 2019 served in either of the two prior legislatures during the tenure of the Congress–led United Progressive Alliance government. Only three — Sonia Gandhi, Rahul Gandhi, and Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury — consistently served in the Lok Sabha during the last four terms.

Explanations for India’s Political Churn

Why do so few incumbent MPs re-run and get re-elected? Three types of explanations account for this phenomenon.

First, political parties have multiple incentives to remove sitting MPs. For instance, they can field fresh faces as an attempt to buck anti-incumbency. Some parties claim to use the spectre of renomination as a reward for high-performing MPs and as a sanction for underperforming MPs. Empirically, there is little evidence that performance predicts a legislator’s chances of renomination. More importantly, the threat of non-renomination is an effective instrument to generate and maintain party discipline and to punish faction leaders and their affiliates. Parties may also discard sitting MPs because of seat-sharing arrangements with other parties.

Second, MPs and candidates themselves can also induce turnover. Some MPs may leave their parties and try their luck with a different party affiliation. Other MPs may drop out of the race altogether if they are unable to sustain the cost of remaining in politics or when they find themselves outspent by adversaries. MPs can also choose to shift to a different legislative body, such as a state assembly or the Rajya Sabha. In the run-up to the 2024 general elections, 28 seats sat vacant after officeholders left the Lower House for the Upper House or passed away so recently that byelections could not be held on time.

Finally, voters also play a role in ensuring that few sitting MPs get re-elected. Across states, the strike rate of re-running MPs is low. In 2009 and 2014, incumbents’ strike rate dropped below 50%. On average, since 1977, only 55% of re-running incumbent MPs have been reelected. The propensity of voters to reject incumbents manifests the structural discontent that elected representatives face. The author’s repeated interactions with MPs over the years reveal that MPs are expected to respond to endless demands and requests for assistance emanating from their constituencies, using limited resources or infrastructure. When considered alongside a high degree of local electoral volatility, such discontent likely accounts for the poor performance of most re-running MPs.

India’s Small Professional Political Class

The flip side of the high turnover of elected representatives is the constitution of a small-size class of professional politicians (MPs who have been elected more than twice). In India’s 17th Lok Sabha, 120 MPs fit this description, a number that has fluctuated over the years. Of those 120 MPs, 69 belong to the BJP, while only 14 belong to the Congress. There are only 36 regional party MPs who can claim to have significant legislative experience.

More worryingly, there are few women among this political class. In the 2019 general elections, 78 women were elected to the Lok Sabha, but only 12 were elected for a third term or more. Members of this stable political class are more likely to be older, hail from dynastic political families, and belong to the upper or intermediary castes than historically disadvantaged groups. This category of elected representatives includes top party leaders and their family members, as well as members of parties’ various high commands. There are only a few representatives whose popularity enables them to weather the electoral misfortunes of their own parties. The small size and enhanced elite profile provide a measure of the degree of concentration of political power in India. The production of this small class of professional politicians is a pan-Indian phenomenon, not specific to any region or any party.

The BJP now makes up more than half of India’s stable political class, a category that the Congress dominated until the mid-1990s. Regional parties started contributing to that category of representatives a decade after their emergence phase in the 1990s. Their share of India’s professional class has reduced over the last three general elections largely due to the decline of regional parties in northern India.

Implications

Low rates of individual incumbency — and the concentration of power it implies — have wide-ranging implications for the functioning of Parliament, the ability of the institution and its members to act as a check on the executive, the meaning of political representation, and the functioning of India’s democracy at large.

On the one hand, short political careers disincentivise newcomers from investing in the legislative aspects of their job. As related research shows, elected representatives typically focus instead on constituency service and on raising the resources necessary to have a career in politics. On the other hand, the combination of high barriers to entry and the high probability of early exit creates incentives for rent-seeking behaviour as the costs of campaigning explode.

The rapid turnover of elected representatives also means that descriptive representation is detached from the individuals meant to embody it. Descriptive representation is reduced to representatives’ caste or community identities but not to the representatives themselves. Descriptive representation can only be effective when Parliament itself is effective as an institution. The concentration of power within parties, and the executive’s dominance of the legislature, hollows out political representation and limits the ability of legislators to induce change or impact.

The transient character of political careers in India contextualises the poor functioning of the Lok Sabha. Data compiled by PRS Legislative Research show that the annual average sitting days of the Lok Sabha have consistently declined: The most recent session hit a record low, utilising just 55% of allocated time. Parliamentary committees rarely meet, and bills are barely discussed.

Other factors contribute to the marginalisation of elected representatives and, by extension, of political representation.

First, parties announce their candidates late in the campaign, sometimes just days before polling. They reshuffle candidates until the last moment, preventing voters from thoroughly understanding who is really running for office.

Second, the anti-defection law has also tamed the ability of MPs to enjoy agency as autonomous lawmakers.

Third, the professionalisation of campaigns and the rise of political consultants have led to the marginalisation of individual candidates. In private interviews, many aspirant candidates and sitting legislators have expressed anguish regarding their exclusion from decision making within their party and within government, more generally.

Finally, the decline of stable political representation resonates with other findings regarding the sociology of India’s political class, which reveal that despite parties’ claims of political inclusion, India’s political leaders tend to be homogenous in class terms.

What is striking is the long-standing character of these trends. The hollowing out of political representation in India is not simply a product of recent democratic decline but also a feature of political representation that gets exacerbated under single-party dominance.

Unsurprisingly, individual incumbency is lower during periods of single-party majorities; in fact, it was even lower when the Congress was in power in the 1950s and 1960s. Greater political competition and the negotiation of power-sharing arrangements at the federal level tend to bring in more experienced politicians, something that is sorely lacking in the current environment.

Gilles Verniers is the Karl Loewenstein Fellow and visiting assistant professor of political science at Amherst College and a senior fellow at the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi. In the weeks ahead, the Carnegie-HT “India Elects 2024” series will analyse various dimensions of India’s upcoming election battle.

Get Current Updates on India News, Elections 2024, Lok Sabha Election 2024 Live, Election 2024 Date, Weather Today along with Latest News and Top Headlines from India and around the world.