This article was featured in CNN’s What Matters newsletter. Sign up for free to get it delivered to your inbox. here.

CNN

—

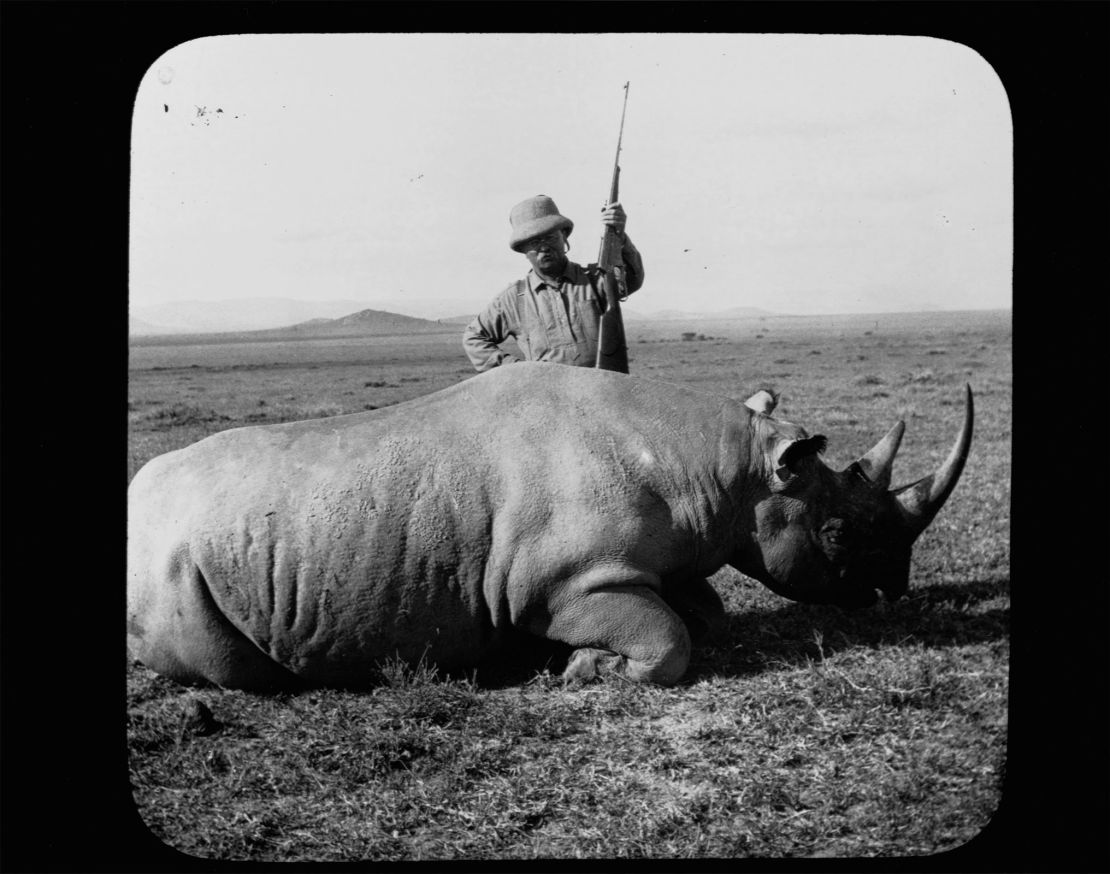

Theodore Roosevelt carefully crafted an image of rugged masculinity: wealthy heir turned badlands cowboy, volunteer rough rider, and war hero.

As a president, Roosevelt was a populist and reformer who was incredibly popular during his lifetime, dissatisfied with the direction of the Republican Party after he left office, split off as a third-party candidate, and nearly won the election in 1912 as the progressive “Bull Moose.” He nearly remade the American political system.

But that picture is incomplete, says a new biography, “The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt: The Women Who Made a President,” written by Edward O’Keefe, CEO of the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library Foundation, which is building a new Roosevelt library in the Badlands of North Dakota, and a former colleague of O’Keefe’s at CNN.

The book argues that the women in Roosevelt’s life have not received the historical attention they deserve, and O’Keeffe proves this with detailed research and engaging prose.

I spoke with O’Keefe about the book and how Roosevelt and his definition of masculinity are relevant today. Our phone conversation, edited for length, follows.

wolf: Your book is about the women behind some of our most notoriously masculine presidents. What were you trying to do with this book?

O’Keefe: “The Love of Theodore Roosevelt” argues that the manliest president in American memory was actually the product of unknown, extraordinary women.

Theodore Roosevelt is memorialized in marble on Mount Rushmore, and there is a myth that his incredible success in both his personal and political life was entirely down to his own will. That is true, but it is not the whole truth.

His two sisters, Bamie (Anna) and Connie (Corinne), his two wives, Alice and Edith, and his mother, Mitty (Martha), were essential to his success, yet their stories have been almost completely lost to history.

wolf: The theme is very clear: These women supported this most famous American man. And yet so much of his life is built around abandoning them. He wasn’t there when his first wife gave birth. He left his second wife, who was critically ill, to join the Rough Riders. He goes on safari, he’s in the Badlands. He’s pretty much disappeared. How do you reconcile that with the larger themes of the book?

O’Keefe: I’m so glad you noticed that. I had an interesting conversation with Connie Roosevelt, wife of Theodore Roosevelt IV (Teddy’s great-granddaughter).

When I first met Connie in 2019 at a fundraiser for the National Parks Conservation Association, I had just begun research for the book that became “Theodore Roosevelt’s Loves,” and I said to her pretty much the same thing you say: Theodore Roosevelt had a pattern of absence. He often died in emotionally difficult circumstances.

And she chuckled and said, “When the going gets tough, the tough go hunting,” which is a phrase I actually use in the book. Theodore Roosevelt was known for enduring physical pain, but that tenacity of cowboys and ranchers really fades when the going gets tough emotionally.

He essentially abandoned his daughter for the better part of three years, giving her to his sister, Bamie, to raise. He later spoke of his exploits in Cuba, saying he would have left his wife on her deathbed to be there, and this was no exaggeration.

I think the women in his life understood that he needed a support system, especially emotionally, that he didn’t necessarily have, and if there’s one thing that’s surprising about Theodore Roosevelt in Love , in addition to the argument that TR was in fact the product of women, it’s that he was an incredibly emotional person, as caricatured in history.

I love Robin Williams and his portrayal in “Night at the Museum,” but that’s a cartoon of Theodore Roosevelt. It’s easy to lampoon him with the big smile and the teeth and the hat and the cowboy thing. However, he is a very sensitive, emotional and deeply feeling person.

I think that’s what gave him the ability to empathize with people. It’s what gave him the ability to connect with people. And it’s all a direct result of the influence of his mother, Mitty, who, by the way, has been completely forgotten in history.

wolf: The main lesson of the book is the gender inequality of the time, but also inequality in general. Roosevelt was born into a family of great wealth, the kind of people who traveled to Europe for months as a child. He was never wealthy, but he escaped that perception to become a populist leader. Inequality is a big problem today, How do you view his rise from that perspective?

O’Keefe: Theodore Roosevelt is not a Horatio Alger story: he did not rise from humble beginnings to the pinnacle of power and wealth in America.

Interestingly, during the Victorian and Gilded Ages, the people with the most wealth To society Roosevelt owed almost nothing to the American people. Theodore Roosevelt, like his distant relative Franklin Roosevelt, was seen as a traitor to his class. It was highly unusual for a man of his status and wealth to run for public office.

Politics was seen as a dirty business, something that only the middle class, lower class and immigrant classes were interested in. Because, why should you have the right to vote? You have wealth, you have influence.

I think part of that was the influence of his parents, Mittie, a Southerner, and See, a Northerner. They were able to overcome their differences without any unpleasantness about one of the most contentious issues in American history, the Civil War. He saw that they were united as a family, and that they cared about the unity of their family as well as the nation.

He had a noblesse oblige mentality. He believed that to whom much is given, much is required. I think that came from his experience in the North Dakota Badlands, where it didn’t matter if you were rich or not, you were expected to work as an equal with the person next to you. The herding horses don’t really care if you’re from the East Side of Manhattan. You either survive and work, or you don’t.

wolf: What struck me most in the book was the description of a situation in which his first wife died in childbirth and his mother died on the same day in the same house. I was trying to quantify the level of tragedy and the first person that came to mind was the current president. Joe Biden loses his wife and daughter This was shortly after he was first elected to the Senate. Did you notice the connection?

O’Keefe: That is absolutely true. Losses are often challenges in an individual’s life that no one wants to experience.

In Theodore’s case, after his father’s death, his mother, Mittie, told him, “We need to live for the living, not for the dead. If we don’t live a purposeful life, we dishonor the memory of those who have died.”

And I think that’s very similar to President Biden’s situation, where, you know, he ran for the Senate and then held that seat for 36 years, but only because he would be a disgrace to the memory of his wife and his daughter.

Loss and chance, fate and luck play an incredible role in American history, and we have to see these moments, these trying moments, not just as turning points in the lives of individual politicians, but how they are intertwined with the destiny of the nation.

wolf: Recently, especially on the political right in America, there has been an increase in men trying to reassert masculinity. Josh Hawley, a Missouri senator who wrote a book about Roosevelt, recently said: The book “Masculinity” What do you think Roosevelt, for example, would think of such a trend?

O’Keefe: That’s exactly what he was experiencing at the time. When Roosevelt was born in 1858, there was no electricity, no cars, no airplanes, no submarines. He would be the first president to fly, drive, travel overseas, and ride in a submarine.

Everything changes, right? Society is moving from an agricultural to an industrial one. The technology that has arrived during this time is disrupting people’s sense of self, connection, and community. There are waves of immigration within the country that are, in many people’s eyes, redefining what it means to be an American. And there is a raging debate about whether we are an isolationist nation or whether we will become a global power.

Does any of this sound familiar?

All of this intersects with masculinity and gender roles, right? There are certain themes around masculinity: how to be a man. What does it mean to be a man? What do you have to do physically to show that you’re a man?

He projects the archetypal ideal of masculinity expected by society in the early 20th century, but what I show in “The Man Who Was Theodore Roosevelt” is that he also had an incredibly emotional and tender side, one in which women helped him achieve his goals despite the constraints of the times.

To your question of what’s going on now, people are trying to understand gender roles, manhood, masculinity. Instead of seeing it as a continuum, they’re trying to define it as one or the other. If you pay attention to history, to me it sounds like something you’ve heard before.

wolf: There’s a scene in the book where Roosevelt has just had a fight with his childhood sweetheart and future second wife, Edith, and in a fit of rage while riding his horse home, he shoots a neighbor’s dog. As I was reading that passage, I immediately thought of the governor of South Dakota. Kristi Noemis facing intense backlash for writing a memoir about shooting her unruly dog. The 19th century is obviously a different time, but when you read about Dakota Sen. Noem, do you think of Roosevelt? Maybe she just lives a “tough life.”

O’Keefe: There’s a big difference between what the South Dakota governor calls a family pet and a neighbor’s animal running around the woods in Oyster Bay, New York.

But such was the duality of Theodore Roosevelt, one of the most moving places to visit today when you go to Sagamore Hill is the pet cemetery, which contains the graves of many of Roosevelt’s beloved animals, many of whom were his pets.

The Roosevelts kept a zoo of animals in the White House, including a badger named Josiah and a snake named Emily Spinach, kept by their daughter Alice and named after her mother. She didn’t like her Aunt Emily, and Emily didn’t like spinach, so this snake must be Emily Spinach, and so it was named. Algonquin is a pony that was taken to the second floor of the White House.

Both the Sagamore and the White House had many dogs in their homes, so the pet cemeteries are filled with the names of beloved family pets.

So while this seems at odds with Theodore Roosevelt’s attitude towards pets and animals, it is certainly true that after breaking up with Edith he became enraged and shot the dog while riding horseback through the woods around Oyster Bay, a perhaps unusual parallel to today’s story.