The key operational question before us is not, “Is Joe Biden too old?” but, “Can we trust the delegates to the Democratic Convention in Chicago to replace the current candidate with one who has a better chance of winning without devastatingly splitting the party?”

On this issue, I am reminded of the striking definition of a conservative offered by the Civil War veteran and author Ambrose Bierce: “A person who is fascinated by existing evils, as distinct from liberals who wish to replace them with other evils.” So call me an Ambrose Bierce conservative.

Here’s just one data point to keep in mind: Joe Biden beat Donald Trump in 2020 primarily because Biden did much better among white men than Hillary Clinton did in 2016. In 2016, Trump won white men’s support by 30 points, but in 2020, Trump won white men’s support by just 17 points.

I have noticed that as Democrats speculate about alternative candidates for this election, they speculate about combinations of presidential and vice presidential candidates designed to stimulate different elements of the party’s base. But Democrats do not have a single “base” any more than Republicans do.

Educated city folk are one base of the Democratic Party. Church-affiliated black voters in the South are another. Labor unions, especially in the industrial Midwest, are a third. The Democrats are a coalitional party, not a base party. That’s why we need coalitional leadership.

Biden, despite his obvious weaknesses, has offered just that, and one of the reasons so many committed Democrats are ready to reject him now is because they don’t like his leadership of the coalition.

“Democrats fall in love, Republicans follow” is an old joke that has been reversed in 2020. Republicans loved Trump. Democrats embraced Biden. Now Democrats are tired of love and yearn to fall in love again.

The need to fall in love is why you won’t hear Roy Cooper, the two-term governor of North Carolina, a purple state. The need to fall in love is why you won’t hear much about Governor Katie Hobbs of suddenly purple Arizona, or Amy Klobuchar, the three-time senator from Minnesota, or even Andy Beshear, the two-term governor of Kentucky, the Democratic Party’s big hope. These are staid, moderate figures who don’t energize activist groups in the same way that the more commonly mentioned names do. No one knows whether a list of candidates that includes two of these people would actually perform better than the Joe Biden-Kamala Harris combination, but there is reason to hope that they would, rather than the more commonly mentioned activist names.

The problem is that the Democratic lobby has strayed far from the basis on which American elections are decided. Cooper wants to sign trade deals even though the party doesn’t trust him. Hobbs is tough on immigration and border security. Klobuchar is a former prosecutor who wants more cops on the streets. Beshear avoids mentioning climate change and appeals to coal country.

But the point is not that these people, or any of the emerging centrist Democrats like them, are necessarily better than the Biden-Harris combination. Biden has been tested in years of national elections; we know his strengths and weaknesses. The other candidates have not been tested, and no one knows how they will actually perform.

Presidential primaries are designed to do just that, but the popular ones attract attention not because they won popular states or tough elections, but because they perform well on TV, are endorsed by activist groups, or fit preconceived ideas about how to mobilize this constituency or that constituency.

Political TV personalities and commentators are valued for being bold and unexpected. These speakers and writers are heavy consumers of political information and tend to react quickly and loudly to new developments. Most voters react more slowly and quietly, if at all.

Political experts often worry about ordinary voters’ attachment to figures and celebrities, but it is the experts who know politicians’ personalities best. For less-engaged voters, parties are powerful brands, and their image is resistant to change.

By contrast, individual candidates take years of work to establish even the vaguest of identities. Trump has been a flamboyant American icon for more than four decades. Biden has been at the forefront of politics for even longer, first as a senator, then vice president and now president. If Democrats were to hastily change their nominee, they would very likely choose someone most Americans would never know, or, worse, someone defined by Trump and backed by hundreds of millions of dollars in Republican campaign funds.

A smart challenger always wants to keep the spotlight on the incumbent and his failings. The problem? The incumbent. One of Trump’s biggest flaws as a political candidate is his constant craving for the spotlight. Until last week’s presidential debate, both Trump and Biden practically agreed that the 2024 election should be a referendum on Trump. Biden’s poor performance that night focused the attention on Biden and his weaknesses. And Trump had the restraint not to distract from the spectacle of his opponent inflicting self-inflict injury. Since then, Trump has been able to keep quiet while the Democrats have engaged in more self-inflicted acts.

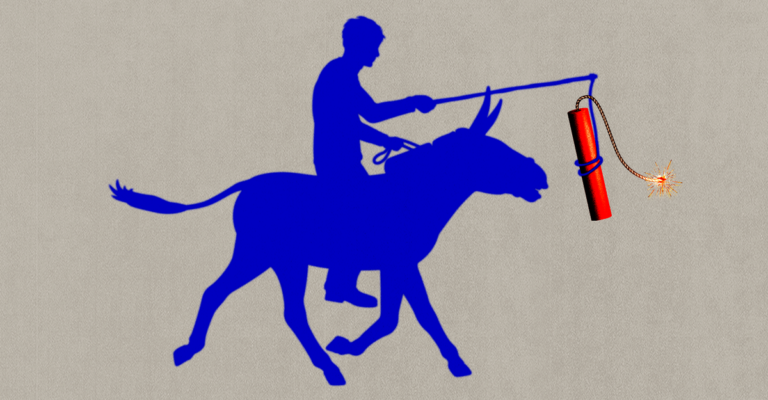

Trump won’t even need that restraint if Biden is removed and the Democrats plunge into civil war over who will replace him. The story will be Democratic disaster all the way. The story told about the Democrats after Biden is removed will not be about their impressive track record in job creation after 2021, or above-inflation wage increases for low- and middle-income workers, or funding for infrastructure and a green economy, or their success in reducing crime. There will also be no talk of Republican vetoes on immigration enforcement, or Biden’s rebuilding of relationships with Democratic allies, or the Democrats’ tireless efforts to protect women’s freedom, or the party’s support for Ukraine and Israel in their respective nations’ wars of self-defense. The story will be one of chaos, fratricide, and division along lines of race, gender, and ideology.

The news isn’t always good. The fight isn’t always easy. Sometimes you get hit, and sometimes the hits are deserved (and they may be the ones that hurt the most). So what happens? The answer to that question is what General Ulysses S. Grant said after the Union army’s disastrous first day at the Battle of Shiloh in 1862: “Tomorrow we’ll beat them.”