Rodrigo Castro Cornejo discusses the reasons for the rise of left-wing populism in Mexico under the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, how López Obrador’s government has transformed Mexico’s political economy during his six years in office, and what this means for the future of populism in Mexico as voters head to the polls on June 2nd.

This article is part of a series seeking to understand the political and economic issues driving populist movements around the world as the “election year” progresses. We will publish a new article every week. You can find it here.

For the past decade, Mexican populism has been defined by Andrés Manuel López Obrador and his leftist party, MORENA. Left-wing rhetoric condemning neoliberalism characterizes López Obrador’s version of populism, but actual policies reflect a range of ideologies, including austerity. In this article, we explore the dimensions of López Obrador’s populism, the economic reasons why voters supported it, and what this means for the future of populism in Mexico ahead of voting day on June 2.

The Rise and Rhetoric of Andrés Manuel López Obrador

Until the 2018 presidential election that brought MORENA and Lopez Obrador to power, Mexico’s party system was one of the most stable in Latin America. Since Mexico’s transition to true democracy in 1997, the centrist Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), the centre-right National Action Party (PAN), and the centre-left Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) have competed as Mexico’s three major political parties. However, corruption scandals and mixed economic, income and employment growth under the PRI and PAN administrations have left voters dissatisfied with these parties.

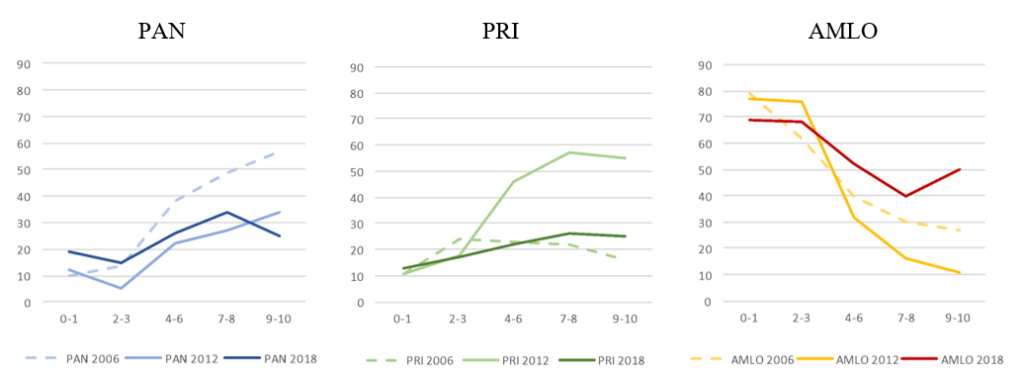

In 2018, MORENA and its presidential candidate, Lopez Obrador, won both the presidency and a majority in Congress through their partisan coalition in Congress. Lopez Obrador won 54.7% of the vote in the presidential election, after winning 32.4% in 2012 and 36.1% in 2006. Lopez Obrador was elected president on his third try by appealing to a broad, multi-class coalition of voters. He received support from men and women, less and more educated voters, younger and older generations, and rural and urban voters alike. But what is most remarkable is how much of his victory was attributable to his appeal to conservative voters. In 2006 and 2012, he won 27% and 11% of the vote from those who self-identified as the most conservative on a 0-10 left-right scale. In 2018, he won 50% of the vote from this age group, according to the Mexican Electoral Survey (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Voting rates for PAN/PRI/AMLO by ideological group (2006-2018)

Lopez Obrador was able to appeal to a wide range of voters by avoiding clear policy proposals as a candidate. Instead, he targeted the corruption of the PRI and PAN governments that had been in power since 1997, arguing that their neoliberal policies were responsible for the lack of economic growth and widespread poverty. Indeed, Lopez Obrador’s 2018 victory may have had more to do with voters’ rejection of the mainstream parties, especially the PRI and PAN, than with the appeal of his policies outside of the option for change.

As a candidate and president, Lopez Obrador has emphasized economic policies that advocate for helping the poor, strengthening Mexico’s state-run oil industry and infrastructure projects, and fighting corruption, particularly in his anti-neoliberal rhetoric. He has sought to distinguish good citizens from the corrupt elite, the “Mafia del Poder” (political mafia), who stripped him of the presidency in 2006 and 2012 and are accused of impoverishing Mexico through neoliberalism and corruption.

His emphasis on the resonant aspects of politics and economics comes at the expense of social issues such as gender equality, abortion, and LGBTQ+ rights. His government has distributed a morality handbook called “Cartilla Moral” and lamented the “loss of cultural, moral, and spiritual values in Mexico.” Lopez Obrador has also warned against legalizing drugs, and his government has pursued strict policies to stop migration from Central America to the United States. This is a shift from earlier administrations that took a more humane approach to migration and called Mexico a “country of refuge.” However, unlike the United States and Europe, it is fairly common in Latin America for politicians to support left-wing economic policies while dismissing or completely opposing progressive social policies. Hugo Chavez and Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, Evo Morales in Bolivia, Pedro Castillo in Peru, and Rafael Correa in Ecuador are other examples of this trend.

Lopez Obrador’s populism is also notable for the various illiberal actions his government has taken against democratic institutions, including appointing loyalists to the Supreme Court and forcing sitting judges to resign. More recently, he has sought to weaken the national electoral institution, the linchpin of Mexico’s democratic transition, the National Electoral Institute (INE), by slashing its budget. This policy would have forced the INE to make staff cuts and close offices across the country, affecting the INE’s ability to organize elections. The Supreme Court ultimately invalidated most of the electoral reforms promoted by President Lopez Obrador, citing serious violations of legislative procedure.

The Political Economy of Populism in Mexico

Lopez Obrador’s left-wing shift on social issues is echoed in the economic sphere. Indeed, many of the policies he implemented during his term have borrowed heavily from the Washington Consensus, which he opposed. For example, his administration supported fiscal austerity measures (which he called “Franciscan poverty”) and argued that by eliminating corruption and waste, the government would be able to continue to fund social welfare programs without raising taxes. This has led to a widening budget deficit, but Mexico’s overall debt level remains sustainable. From 2017 to 2023, the government deficit grew from 1.1% to 2.95% of GDP (down from a peak of 4.6% in 2020). However, the deficit is projected to reach 5% in 2024 as the government increased social spending ahead of the elections. And despite increased spending during the COVID-19 pandemic, Mexico reported the lowest levels of fiscal support (such as targeted transfers and tax cuts) to mitigate its economic impact compared to its Latin American peers. Moreover, a net of 15 million Mexicans lost access to public health care after Lopez Obrador’s administration eliminated the Seguro Popular program in 2020, a program Lopez Obrador characterized as “neoliberal.” The program was replaced by another program that did not have the same comprehensive coverage. Similarly, while poverty has declined overall under Lopez Obrador’s administration, extreme poverty has actually increased by 400,000 people due to changes the administration made to Mexico’s social welfare programs.

Meanwhile, Lopez Obrador’s administration has made good on some of his election promises, such as replacing Mexico’s conditional cash transfer program, Progresa Oportunidades, with a new program that sends cash transfers directly to marginalized groups such as students, single mothers, and young professionals. Lopez Obrador’s administration has also significantly raised the minimum wage, boosted labor unions, and increased public investments in infrastructure, especially in the country’s poorest region, the south (such as the Mayan train and the Dos Bocas oil refinery).

Indeed, perhaps Lopez Obrador’s most notable achievement is his efforts to foster a revival of Mexico’s state-run oil industry. During the 2018 election campaign, Lopez Obrador denounced the PRI and PAN’s 2013 legal reforms that allowed private and foreign investment in Mexico’s oil, gas, and power sectors, and encouraged private investment, especially in renewable energy. The reforms were aimed at modernizing Mexico’s gas industry and increasing production, which had fallen sharply for years. After taking office, Lopez Obrador reimposed barriers to private and foreign investment in Mexico’s oil sector. Falling global oil prices meant that investment was less likely to be attracted than initially expected, and for many Mexicans, giving up sovereignty over Mexico’s resources was no longer justified. President Lopez Obrador prioritized public investment in the fossil fuel industry, including building a $20 billion oil refinery in Mexico’s poor southern region, and dismantled the publicly funded National Institute of Climate Change. As a result, Mexico is expected to miss its climate commitments under the Paris Agreement.

Lopez Obrador’s economic policies, as well as his stance on social issues, resemble the economic nationalism of Latin American left-wing populists, which emphasizes national dignity and sovereignty through control of natural resources. As part of his energy policy, Lopez Obrador has refurbished old refineries at home and purchased new ones in the United States, stating that the refineries are now “part of the Mexican nation.” At a press conference, Lopez Obrador stated: “We are going to become self-sufficient. [stop importing gas and diesel from other countries] And we’re going to make sure that oil prices don’t go up.”

Mexico’s June 2nd Elections and the Future of Populism

Lopez Obrador’s administration is fairly popular among Mexican voters, with roughly 65% approving of his administration throughout his six years in office. However, support for certain policy areas varies. For example, 62% believe the president is handling social welfare programs well, but approval is much lower on the economy (39%), fighting corruption (38%), and security (29%). The latter two have seen little progress and have even worsened under his leadership. But Lopez Obrador’s low ratings on the latter issues probably don’t matter. As one survey found, voters don’t consider these issues in isolation, but rather in comparison to the future capabilities of MORENA’s main rivals, the PAN and the PRI. They still rate the PAN and the PRI much more negatively. Recognizing this, Lopez Obrador continues to focus the public’s attention on the failures of past administrations rather than the triumphs of his own.

Constitutionally, Lopez Obrador cannot seek reelection in the June 2 vote. MORENA has nominated Claudia Sheinbaum, a former head of government in Mexico City, as his successor. She fully supports “Lopesobradolism” and campaigned in favor of the continuation of the “Fourth Revolution” that Lopez Obrador characterizes as his political movement. Mexico’s first three revolutions are the independence of 1821, the era of secular reform in the mid-19th century, and the 1910 Revolution. Sheinbaum will face Xochitl Gálvez, who was jointly nominated by the PAN, PRI, and PRD. Recent polls show Sheinbaum’s voting intentions at about 55% and Gálvez’s at about 33%.

This means that Mexico is likely to experience a populist government for the next six years. Sheinbaum has campaigned in support of the continuation of Lopez Obrador’s economic policies and political agenda. She has supported controversial infrastructure projects, such as the new oil refinery that the Lopez Obrador administration is currently building. She has also explicitly opposed tax reform and avoided taking clear positions on social issues such as abortion, as Lopez Obrador did in his previous presidential campaigns. And, more importantly, Sheinbaum supports the so-called “Plan C,” a set of constitutional reforms that, if approved, would weaken the Supreme Court as a democratic check on the president as well as the independence of democratic institutions such as the INE, the body that organizes Mexico’s national elections. Under Sheinbaum, Mexico can expect much of the same.

Articles represent the opinions of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.