When Jeff Flake woke up Sunday morning to the news of a political assassination attempt in America, his first thought was Never again.

Mr. Flake, a former Republican senator and now the U.S. ambassador to Turkey, has a history marked by violence. In 2011, his friend Gabby Giffords, then a congresswoman, was shot in the head while speaking to constituents outside a Tucson supermarket from Arizona. A few years later, a gunman opened fire in a Virginia park while Mr. Flake was practicing with other Republicans for the congressional baseball game the next day. Though he wasn’t shot himself, he still remembers the events of that day vividly: hiding in the dugout and using his belt to apply a tourniquet to a wounded congressional aide. The gunshots. The blood on his clothes.

In a phone interview Sunday, Flake said he couldn’t get the memory of the shooting at Donald Trump’s rally in Butler, Pennsylvania, over and over again as he watched it. Pop pop pop “He brought it back for me,” Flake said.

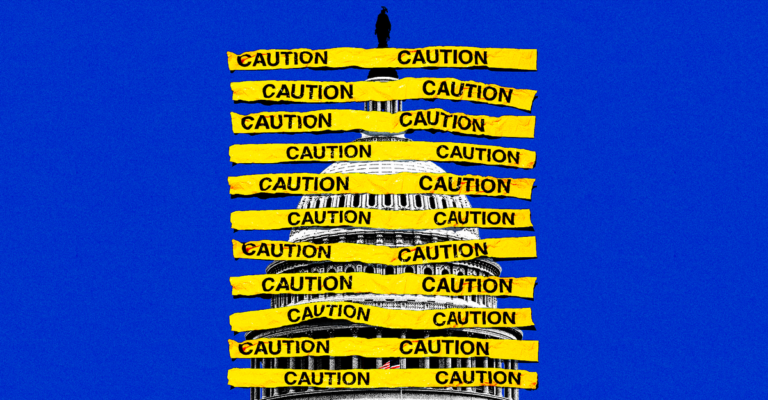

In the days after the assassination attempt on Trump, various leaders and commentators responded by repeating the same assertion: “Political violence has no place in America.” This is a good aspirational statement, but patently untrue as a factual assertion. The Butler shooting fits into a disturbing pattern of violence targeted at U.S. government officials, as my colleague David A. Graham recently detailed. To hold public office in America today is to know that people may try to kill you.

Political assassinations are by no means a new phenomenon, and anyone who has worked in a congressional office or the governor’s mansion can tell you they are taught protocols for dealing with death threats. But early in his career as a congressman in the early 2000s, Flake told his staff not to worry about such dangers. “I would brush them off lightly and say, ‘Bear with it, this is part of the job,'” he told me. But after Giffords was shot, that ended. He realized the threats were real, not just to him, but to his staff, his family, even his supporters. The tone of our nation’s politics — heightened tension, to use a favorite metaphor now — makes this reality hard to ignore. “I never take it lightly,” he said.

The number of close calls in recent years is similarly impossible to ignore. For me, this fact was underscored when I looked back at the politicians I’ve covered for the magazine and realized that many of them have been targets of violence. Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh turned himself in to police at the last minute after a man plotting to kill him showed up at his Maryland home. Former Vice President Mike Pence was rushed out of the U.S. Capitol by the Secret Service on January 6, 2021, as rioters called for him to be hanged. Sen. Mitt Romney narrowly escaped the same mob and then spent $5,000 a day on private security for his family.

It would be naive to think that the constant threat of violence has no effect on the psychology of our elected leaders. When Romney addressed a hostile crowd at the Utah Republican Convention in 2021, he told me he wondered if he was safe. “Some of us are crazy,” he said. And in Utah, “people carry guns… it only takes one really mentally ill person.” If political leaders live in fear of violence from their own constituents, surely it’s only a matter of time before that fear starts to affect their decisions to govern? Romney told me he’d personally spoken to Republicans who wanted to vote for impeachment and conviction of President Trump after January 6 but chose not to, fearing for the safety of their families.

The image of the latest wave of political violence in America will be a symbol of defiance: Trump, bloodied and face-to-face with his fist raised, bravely facing his supporters after a bullet had flown into his head. Already, that image has shaped the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee, where delegates greeted the candidate on Monday night with a bandaged right ear as he made a triumphant entrance into the Fiserv Forum, fists raised in solidarity.

But these strong performances belie the underlying fear that many political leaders must be feeling right now. Flake left public office in 2019 and has spent the past three years abroad, providing a global view of America’s epidemic of political violence. (He recently announced he would be leaving office in September.) “I was talking to a friend in Turkey today, and they don’t expect this from the United States,” he told me. “It’s really sad. They can’t see the United States as a stable democracy that can stand up for itself. They expect that, but it’s really tough right now.”