My country, Rwanda, has long had a reputation for advancing women’s rights and protecting the family, but this approach is highly selective, and critics of the government, like me, are routinely denied those rights and protections with impunity.

The Rwandan Constitution clearly outlines the state’s responsibility to protect the family and provide the necessary conditions for it to thrive. This commitment is institutionalized through the Ministry of Gender and Family, which houses the Family Promotion and Child Protection Directorate. This directorate is tasked with developing comprehensive policies aimed at eradicating gender-based violence and protecting women and children from domestic and other forms of violence. Several of the policies developed by this directorate have played a key role in enhancing Rwanda’s reputation as a defender of women and families.

But there is a huge gap between this ideal policy framework and the reality faced by government critics like me.

My experience as a political dissident in Rwanda for the past 14 years highlights the dire selective application of these rights.

Thirty years ago, I was a student in the Netherlands when the Rwanda genocide against the Tutsi occurred. Horrified by the reports of political turmoil, suffering and death coming from my beloved homeland, I decided to take action and founded a political party called the United Democratic Forces of Rwanda (FDU-Inkingi).

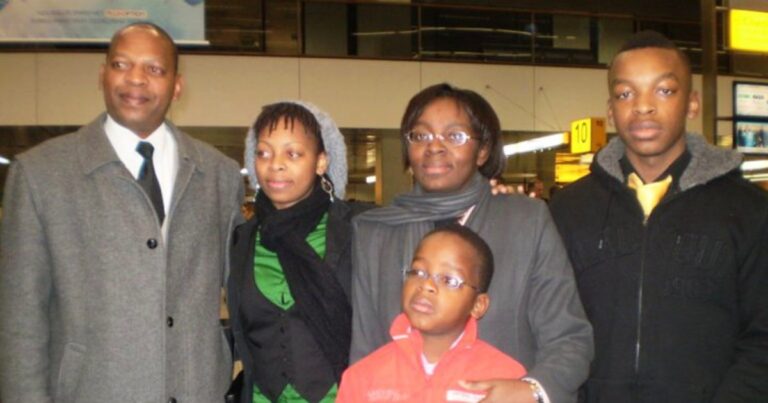

After a long political career in the diaspora, I returned to Rwanda in January 2010, registered a political party and ran against the incumbent President Paul Kagame. I said goodbye to my husband and three children at Amsterdam Airport Schiphol for what I thought would be a brief farewell.

Sadly, 14 years later we remain apart.

My criticism of Rwandan government policies and open political ambitions led to the systematic violation of my civil rights, including the right to a family life.

In March 2010, two months after arriving in Rwanda, I wanted to return to the Netherlands for my son’s eighth birthday. I had promised him that I would celebrate with him and I wanted to keep that promise. However, police stopped me at the airport and told me that I would not be allowed to leave the country because of an impending summons from the Criminal Investigation Department (CID). The CID was subsequently replaced by the Rwanda Investigation Department. This was the first in a series of targeted restrictions aimed at restricting my freedom following my political opposition.

The situation worsened further in April 2010, when I formally asked the Attorney General for permission to travel to the Netherlands for an important family event: my son’s First Holy Communion. I gave the relevant authorities a specific date of travel. CID responded by summoning me for questioning on that exact date, effectively banning me from traveling and attending the ceremony.

By the end of 2010, this political persecution had intensified and I was arrested on trumped-up charges such as “conspiring against the government through war and terror” and “genocide denial” – unfounded accusations in response to my bold participation in Rwandan democracy as a presidential candidate and my speech calling for unity and reconciliation at the Kigali Genocide Memorial in Gisozi.

In 2012, after a politically motivated trial, the Rwandan Supreme Court sentenced me to 15 years in prison, a sentence that further violated my human rights. I had to endure long periods of solitary confinement, which was not part of my sentence, was also allowed limited visits with my relatives, and had limited access to social support networks – all practices that stand in stark contrast to Rwanda’s commitment to protecting families and promoting women’s rights.

In 2014, I appealed to the African Court of Human Rights (AfCHPR). After three years of deliberations, the Court ruled in my favour and acknowledged that my rights had been violated. The 2017 ruling by the African Court confirmed that the Rwandan government had breached its international obligations. The Court further ruled that the Rwandan government should compensate my family for the moral prejudice suffered during this ordeal. To this day, the Rwandan government has not recognised the AfCHPR ruling. After the African Court ruling, I was imprisoned under stringent conditions for a further year, even though I was eligible for release. I was eventually released conditionally in 2018 following a presidential pardon.

However, my suffering and that of my family did not end with my release from prison. After my release, I was subjected to a relentless smear campaign on social media. Many Rwandan officials, including ministers, government spokespeople, presidential advisors, ambassadors and members of parliament, publicly accused me of promoting “genocidal ideology,” “inciting genocide” and waging war against Rwanda and its people. Though demonstrably false, these allegations targeted me and made me fear for not only my own safety but also the safety of those closest to me. These fears were not unfounded and during this period many of my closest supporters who supported my call to establish true democracy and the rule of law in Rwanda were forcibly disappeared, killed or arbitrarily arrested. Though I was not related by family lineage to any of them, they were all family to me and I remain heartbroken that I was separated from them. The children, wives, parents and other families of my supporters who were killed, disappeared or imprisoned for calling for a more democratic Rwanda also live in endless grief. They too have been unjustly denied the right to live as families in a country that has promised to protect them.

The presidential amnesty I was granted in 2018 stipulates that I can leave Rwanda with the permission of the Ministry of Justice. However, my repeated requests to visit my family in the Netherlands have so far been met with silence. Over the years, I have received several “acknowledgments” of my requests but never an actual response. I have missed many family milestones, including my children’s weddings and the birth of a grandchild.

In 2023, I appealed directly to Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame on humanitarian grounds, seeking permission to visit my seriously ill husband whom I had not seen in over 10 years. Again my plea fell on deaf ears. Since then, I have again attempted to have my civil rights restored, including the right to freedom of movement, through the Rwandan courts, but my application was rejected.

Today, as countries around the world celebrate World Parents Day, I remain separated from my children. My story and the stories of my supporters who have been attacked in many ways for their demands for true democracy and the rule of law in Rwanda speak to the harm that parents and children suffer when the institutions of the state are used to silence, intimidate and punish critics of the government and human rights defenders.

Now, not only am I being denied the right to live with my family, I am also barred from taking part in my country’s elections, which means I cannot run and take part in the July 2024 presidential elections and speak out for true democracy, human rights and the rule of law in Rwanda.

The government’s refusal to restore my political rights and repeated violations of my fundamental human rights, including the right to a family life, violate Rwanda’s obligations under the East African Community Treaty, which requires it to uphold the fundamental principles of democracy, the rule of law and respect for human rights.

For this reason, I have filed a lawsuit at the East African Court of Justice. My objective is not only to secure provisional measures to allow me to take part in the upcoming presidential elections, but also to challenge the unjust and painful separation from my family. This lawsuit is not just about my rights, but also to assert the rights of all those who have suffered in the same way, and I hope to be able to celebrate the next World Parents’ Day surrounded by my children.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.