In any competitive field, rivals are constantly striving to do better. They look for innovations that will improve their position, and they try to copy anything that seems to work for their opponents. We see this phenomenon in sports, business, and international politics. Imitation doesn’t mean you have to do exactly what others do, but ignoring the policies that others benefit from and refusing to adapt is a good way to keep losing.

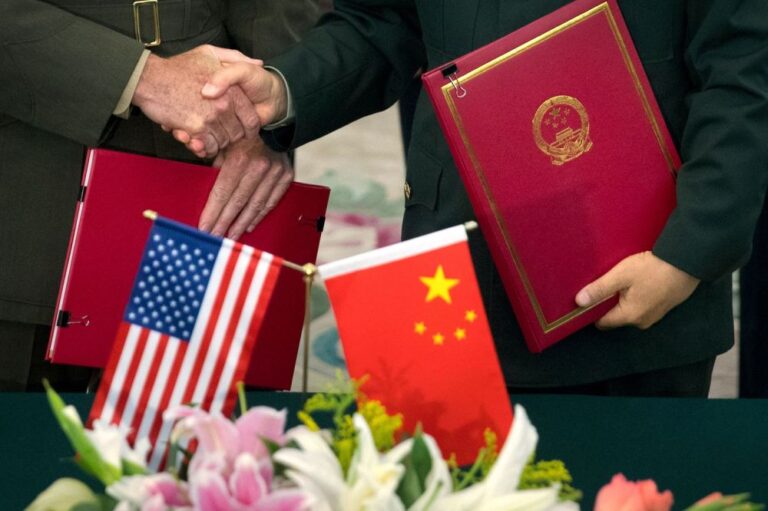

Today, the need to compete more effectively with China is perhaps the only foreign policy issue on which nearly all Democrats and Republicans agree. This consensus shapes the U.S. defense budget, drives efforts to strengthen partnerships in Asia, and encourages the growing high-tech trade war. But beyond accusing China of stealing U.S. technology and violating previous trade agreements, the chorus of experts warning about China rarely considers the broader measures that have helped Beijing get away with this. If China is truly exploiting the United States, shouldn’t Americans be asking themselves what Beijing did right and what the U.S. did wrong? Can China’s approach to foreign policy offer useful lessons for those in Washington?

Indeed, much of China’s rise is purely due to domestic reforms. The world’s most populous country has always had enormous potential, but that potential was stifled for more than a century by deep-rooted internal conflicts and flawed Marxist economic policies. Once its leaders abandoned Marxism (not Leninism!) and embraced market economics, the country’s relative power inevitably grew exponentially. And the Biden administration’s efforts to shape a national industrial policy through the Anti-Inflation Act and other measures reflect a belated attempt to emulate China’s state-sponsored efforts to gain an advantage in several key technologies.

But China’s rise is not just the result of domestic reforms and Western complacency — it is also driven by a broader approach to foreign policy that U.S. leaders would do well to reflect.

First, and most obviously, China has avoided the costly quagmires that have repeatedly bogged the United States down. Even as China’s power has grown, it has been cautious about taking on potentially costly commitments abroad. It has not pledged to go to war to defend Iran, for example, or to defend its various economic partners in Africa, Latin America, or Southeast Asia. While China has supplied Russia with militarily valuable dual-use technologies (and has been highly compensated for doing so), it has not sent Russia lethal weapons, debated whether to send military advisers, or considered sending its own troops to help Russia win a war. Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Putin may often talk about a “no-holds-barred” partnership, but China continues to press for tough deals in negotiations with Russia, most notably by demanding access to Russian oil and gas at bargain prices.

In contrast, the United States seems to have a good instinct about getting into foreign policy quagmires.

Even when it’s not spending trillions of dollars trying to topple dictators or export democracy to places like Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya, the United States is extending security guarantees to countries around the world that it hopes it will never have to defend. Astonishingly, U.S. leaders consider it some kind of foreign policy achievement every time they accept a mission to defend another country, even if that country is of limited strategic value or may not contribute much to advancing U.S. interests.

The United States is now formally committed to defending more countries than at any time in history, and trying to fulfill all of these commitments helps explain why the U.S. defense budget is so much larger than China’s. The difference between Chinese and U.S. spending is over $500 billion, but imagine what the U.S. could do every year. If the U.S. wasn’t trying to police the whole world, it could have the world-class rail, urban transit, and airport infrastructure that China has, and run a smaller budget deficit.

This is not an argument for withdrawing from NATO, severing all U.S. commitments, and retreating to Fortress America, but it does suggest that we should be more cautious about expanding new commitments or insisting that existing allies meet their responsibilities. If China can become stronger and more influential without pledging to defend dozens of countries around the world, why can’t the U.S.?

Second, unlike the United States, China maintains working diplomatic relations with nearly every country. China has more diplomatic missions than any other country, ambassadorial posts are rarely vacant, and its diplomats are increasingly well-trained professionals (rather than amateurs whose primary qualification is their ability to raise money for a winning presidential candidate). Chinese leaders recognize that diplomatic relations are not a reward for others’ good deeds, but an essential tool for obtaining information, communicating China’s views to others, and advancing their own interests through persuasion rather than violence.

In contrast, the United States tends to withhold diplomatic recognition from countries with which it remains in conflict, making it difficult to understand those countries’ interests and motivations and even more difficult to communicate its own. Washington refuses to officially recognize the governments of Iran, Venezuela, and North Korea, even though it would benefit from regular communication with these governments. China, of course, talks to all of these countries, as well as all of America’s closest allies. Shouldn’t we do the same?

For example, China has diplomatic and economic relations with every country in the Middle East, including countries such as Israel and Egypt, which have close ties with the United States. In contrast, the United States has a “special relationship” with Israel (and to some extent Egypt and Saudi Arabia), which means that the United States supports Israel no matter what it does. On the other hand, the United States does not have regular contact with Iran, Syria, or the Houthis, who control most of Yemen. America’s regional partners take U.S. support for granted and often ignore its advice, since they do not have to worry that the United States might reach out to their rivals. For one thing, Saudi Arabia maintains good relations with Russia and China, and has made implicit threats of realignment to extract further concessions from Washington, but U.S. officials are not willing to play the same balance of power politics game against it. Given this asymmetric relationship, it is not surprising that it was Beijing, not Washington, that fostered the recent detente between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Third, China’s general approach to foreign policy emphasizes national sovereignty — the idea that all countries should be free to govern themselves according to their own values. If you want to do business with China, you don’t have to worry about China dictating how you should run your country, or be sanctioned if your political system differs from Beijing’s.

In contrast, the United States sees itself as the leading promoter of universal liberal values and believes that the spread of democracy is part of its global mission. With some notable exceptions, the United States often uses its power to encourage other countries to respect human rights and move toward democracy, sometimes conditioning its support on other countries promising to respect human rights and make further efforts toward democracy. Given that the majority of the world’s countries are not full democracies, however, it is easy to understand why many countries prefer the Chinese approach, especially when China offers tangible benefits. As former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers recalled, “A developing country person once told me, ‘What you get from China is airports. What you get from the United States is lectures.'” If you were an unrepentant dictator or the leader of a less-than-perfect democracy, which approach would you find more appealing?

To make matters worse, America has a tendency to take a moral stance, making it vulnerable to accusations of hypocrisy whenever it fails to live up to its own standards. Of course, no great power can ever live up to all of its professed ideals, but the more a nation claims to be uniquely virtuous, the greater the punishment it faces when it fails to live up to those standards. Nowhere is this problem more evident than in the Biden administration’s insensitive and strategically incoherent response to the Gaza war. Instead of condemning the crimes committed by both sides and using the full extent of U.S. influence to end the fighting, the U.S. provided Israel with the means to wage a vengeful and brutal campaign of destruction, defended Israel in the UN Security Council, and dismissed plausible charges of genocide despite ample evidence and the scathing assessments of the chief prosecutors of the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court. And all the while, it maintains how important it is to maintain a “rules-based order.” The fact that these events have significantly tarnished the image of the United States in many countries in the Middle East and the Global South, from which China has benefited, should surprise no one. Astonishingly, U.S. officials have yet to make a clear statement about how America’s response to this tragedy makes Americans safer, more prosperous, and more respected around the world.

After all, China’s emergence as America’s main rival was partly due to a more effective mobilization of its potential power, but also to limiting its engagement abroad and avoiding the self-inflicted wounds suffered by previous U.S. administrations. That doesn’t mean China’s record is unblemished; far from it. Xi Jinping was wrong to publicly abandon the policy of peaceful rise, and his highly nationalistic “wolf warrior” diplomacy alienated countries that had previously welcomed closer ties with Beijing. The much-touted Belt and Road Initiative was at best mixed, generating both goodwill and badwill, and creating significant debts that Beijing will have a hard time recovering. Its tacit support for Russia in Ukraine tarnished China’s image in Europe and triggered governments to retreat from closer economic integration. And China has not always delivered on its commitments to the principle of national sovereignty.

But Americans who are deeply concerned about China’s rise should reflect on what Beijing did well and what Washington did not. Here’s the irony: China has risen so quickly by imitating the United States, which once rose to the top of world power. As a rising power, the United States had many innate advantages—a fertile continent, a sparse and fragmented indigenous population, and the protection of two vast oceans—and it made the most of those assets by avoiding trouble abroad and building strength at home. The United States fought only two foreign wars between 1812 and 1918, and its opponents in those wars (Mexico in 1846, Spain in 1898) were weak states without powerful allies. And once it became a great power, it let other great powers balance each other out, stayed out of conflict for as long as possible, and “won the peace” by minimizing damage in both world wars. China has been following a similar path since 1980, with great success so far.

German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck once said, “Only fools learn from their own mistakes; wise men learn from the mistakes of others.” His statement can be amended to read, “Wise nations learn not only from the mistakes of others, but also from what they do right.” The United States should not try to be like China (though former US President Donald Trump clearly envies China’s one-party system), but it could learn from Beijing’s more pragmatic and self-interested foreign posture.