PUBLISHED

July 27, 2025

Iftikhar Siddiqui, a 55-year-old resident of North Nazimabad’s block S, has been mugged multiple times over the last two decades. The first time he was robbed was in 2004 when he was on his way to the bakery across the street. “I was using the bakery’s PCO for a call when a man approached me, snatched the phone receiver and slammed it shut.” Pressing a gun against his chest, the mugger slapped Siddiqui, took his phone and wallet, and instructed him not to move. For the next 30 minutes, the robbers mugged every customer entering the bakery.

At the time, Iftikhar didn’t file an FIR, believing his belongings wouldn’t be recovered. The experience shook him so deeply that he avoided going to the bakery for a while. But the trauma didn’t end there. In January 2020, he was mugged again, this time outside his home. He immediately called the Citizens Police Liaison Committee (CPLC) to get his SIM cards blocked, fearing they’d be misused.

The recurring incidents have left Siddiqui gripped by anxiety whenever he steps outside. “Every time a pedestrian or motorcycle comes near, I get extremely nervous — I think I’m about to be mugged again,” he shares.

Fear and anxiety have become a part of life for the people of Karachi. No matter the time of day or location, they live with the looming threat of street crime because they know no citizen is truly safe.

Karachi has constantly grappled with violence and crimes over the decades. The city frequently finds itself listed as one of the most dangerous cities in the world. In 2013, the Karachi operation, a targeted law enforcement campaign, was launched to curb rampant crime, violence, and terrorism in the city. While it is difficult to determine the full impact of the initiative, for argument’s sake, it can be said that it temporarily stabilised law and order in Karachi. However, since 2020, the city has once again found itself battling a rising tide of street crime.

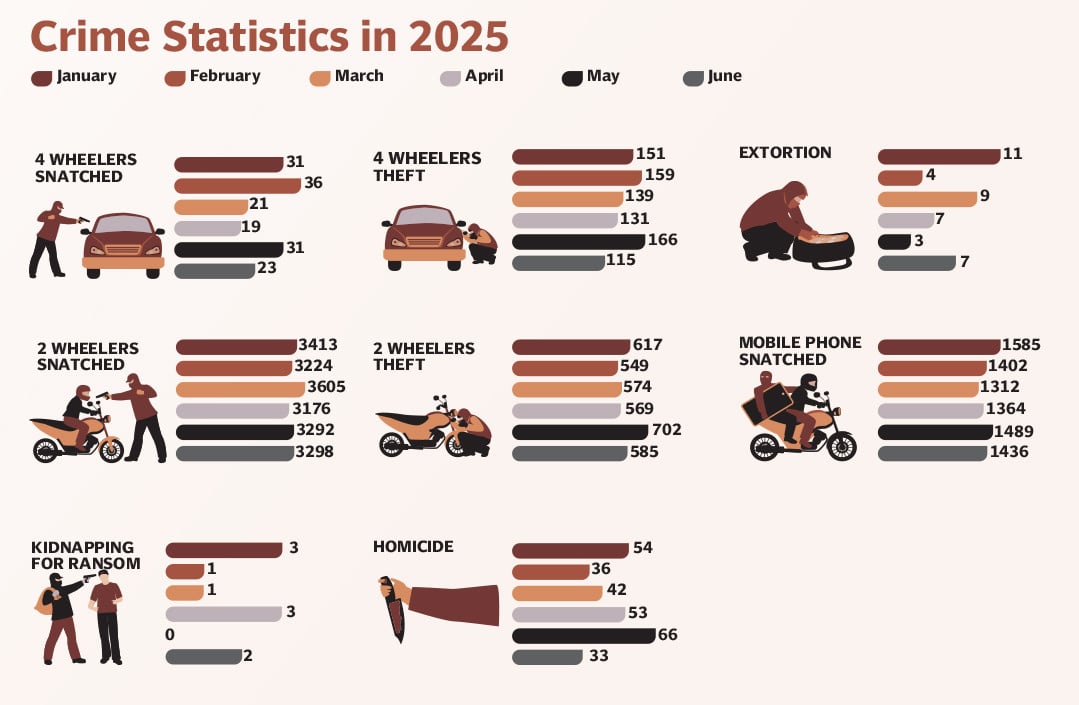

Between January and November 2024, Karachi recorded 66,530 such incidents, averaging 6,048 per month and 199 per day, according to CPLC data. These included 1,913 car thefts/snatchings (6 daily), 46,404 motorbike thefts/snatchings (139 daily), and 18,213 phone snatchings (55 daily). Based on this trend, the total number of incidents in 2024 alone likely exceeds 72,000.

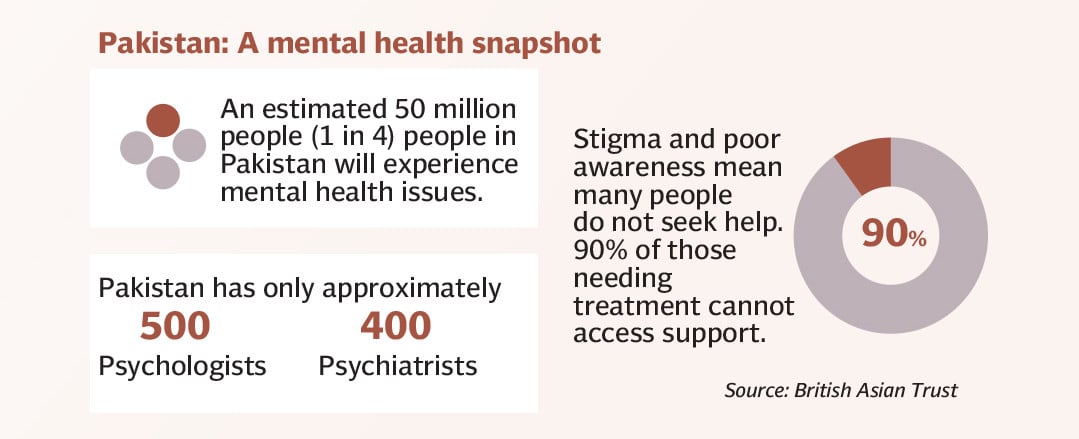

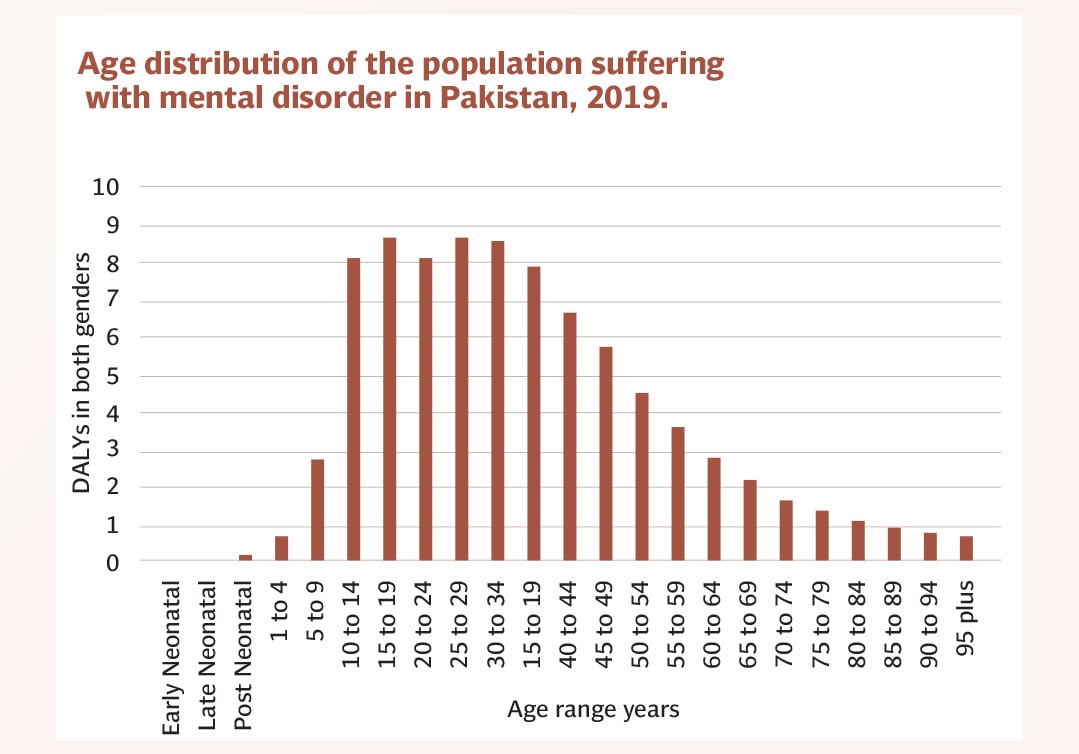

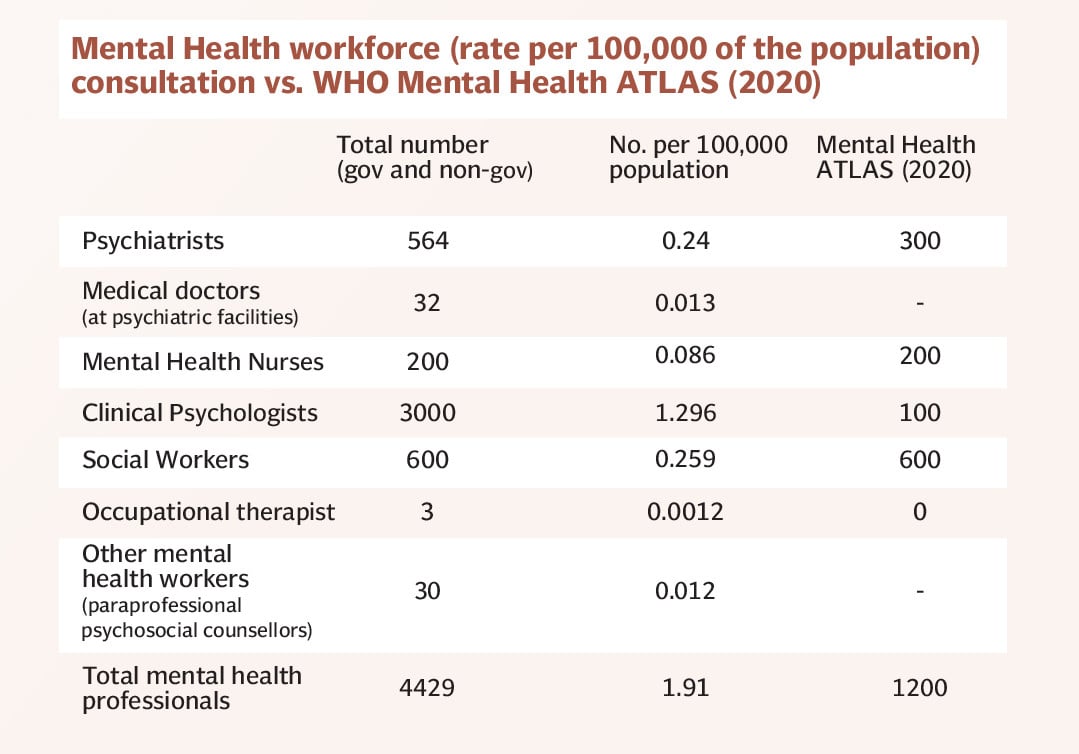

The mental health repercussions of street crimes are often overlooked but profoundly significant. Kinza Shamim, a trauma therapist who practices in Karachi, explains that anyone who has experienced or witnessed a street crime may face long-term mental health effects. “If an incident has strongly affected an individual, it can likely transform into a disorder such as anxiety or depression,” she says.

Sinister tactics

Over the years, criminals have become more organised and creative. The criminals’ tactics have become regular dinner table conversations, reflecting how deeply ingrained and pervasive the fear has become in everyday life.

Initially, robbers approached pedestrians asking for directions or would jump off vehicles to mug victims before fleeing. Now, they attack in groups at roadside eateries or set up roadblocks on busy streets to loot passing vehicles. In 2022, for example, 10-12 robbers blocked the Korangi Causeway and robbed over 100 people. Motorcycle robberies remain the most common tactic.

Shamim explained that street crimes don’t just affect individuals but can lead to a collective sense of helplessness and trauma within communities. This is echoed on platforms like Numbeo.com, which tracks global crime and safety perceptions. Karachi’s page shows a high concern rating of 67.10 for the risk of being mugged or robbed, highlighting how deeply ingrained this anxiety is among the city’s residents.

In November 2023, 30-year-old Usman*, a pharmacy technician at Sindh Infectious Diseases Hospital, was mugged during his commute. “I usually avoid taking the bus, but I didn’t have a choice that day,” he said. As he tried to get off a packed bus, a man blocked the door. Usman squeezed past but soon realised his phone was missing. He grabbed a man behind him, suspecting theft, but was outnumbered and forced to back down.

At work, he called his phone from a colleague’s mobile; it rang briefly before being switched off. Seeing little point in filing a police report, Usman blocked his SIM cards and phone online.

“My phone cost 30,000 rupees, but the bigger loss was the unbacked-up data and documents,” he shared. Without his educational and work-related certifications, Usman has faced several problems. “I can’t list those qualifications on my CV since I have no proof. I was also supposed to receive a Higher Education Commission-certified document on my email, which was logged into the stolen phone.”

The harassment on the bus and the loss of his data still weigh heavily on him. “Commuting by bus is highly unsafe now. It’s a coordinated effort, while one distracts you, others rob you.” Usman’s story highlights the daily threats faced by thousands of commuters. Many similar stories remain untold as countless people lose valuable belongings and data to criminals.

Women, in particular, face an added layer of risk — their devices often contain photos and videos, which criminals sometimes exploit to blackmail them further and extort more money. This reveals how citizens are constantly caught in a state of severe stress, always trying to stay vigilant.

Impact on business and daily life

The lawlessness in the city has affected everyone, including traders and businessmen who are frequently mugged outside their workplaces or banks. “The constant insecurity has contributed to a sense of despondency, compelling businessmen to either relocate within Pakistan or abroad,” says Faisal Sarwar, an economist and educator.

Mounting safety concerns often compel traders to reduce operating hours. Farhana*, 60, who runs a small bed-linen store in Bahadurabad, says customers avoid visiting early in the day or late in the evening due to the increased risk of muggings. “Customers carry less cash with them, which has affected sales.”

She shared how a fellow shopkeeper once foiled a mugging by flashing his licensed pistol. “Many shopkeepers now close earlier and leave together at night to avoid snatchings,” Farhana added. Having narrowly escaped two mugging attempts herself, she fears for her safety, particularly during commutes, and believes her business is suffering as a result. “Without accountability,” she said, “nothing will change.”

Traders across various bazaars raised similar concerns, adding that in an already fragile economy, the fear of being mugged further discourages customers from shopping freely and business owners from taking risks. As some scale back investments or shut down entirely, the ripple effects are clear: reduced economic activity, job losses, and a weakened urban economy.

Eroding trust

Robbers target people indiscriminately, from pedestrians to street hawkers and even law enforcement personnel. A hawker from the Sabzi Mandi area said that groups of 8 to 10 robbers often block streets early in the morning, mugging both hawkers and passersby. They even target truckers coming from the highway. “I’ve lost significant amounts of money because of this, and I don’t even make enough,” he said. He now sets up his stall later in the day to avoid such incidents.

Instances where government and police officials themselves have fallen victim to robbers suggest that criminals are operating with impunity. Like shop owners, many other citizens have taken matters into their own hands by arming themselves and confronting criminals. Moreover, instances of suspects escaping custody have further eroded public trust. In June 2024, the prime suspect in the murder of Itteqa Moeen, a mechanical engineer fatally shot by robbers in Gulshan-i-Iqbal, escaped from the City Courts lock-up after a court appearance.

Over the years, political figures and law enforcement personnel have offered various explanations for street crime, with some normalising it by claiming that most metropolitan cities face high crime rates. One example is from September 2022, when former AIG Javed Alam Odho claimed that Karachi’s crime rate was lower than several cities in the US and India. The provincial government also portrayed Karachi’s street crime problem as an insurmountable challenge worsened by migration and ethnic divisions. However, the reality is starkly different; governmental deficiencies and a lack of decisive action involving all stakeholders perpetuate street crimes in Karachi. Without serious and concerted efforts to address these issues, the problem will persist.

Bridging gaps

According to Murad Soni, social activist and community police Karachi chief, most people don’t report street crimes because the process involves extensive paperwork with little to no outcome. “Victims are often left thinking, what’s the point? Nothing ever comes of it,” he says. This widespread disillusionment with the justice system deepens the mental toll, reinforcing a collective sense of helplessness and vulnerability.

Part of the issue, Soni explains, is that Karachi’s policing system lacks both manpower and basic resources. “Street criminals know the chances of being caught, let alone convicted, are slim,” he adds. Even when arrests are made, suspects are often released within days, further undermining confidence in law enforcement.

Still, small wins exist. In certain blocks of North Nazimabad, Soni’s CPK has seen a notable drop in crime after installing CCTV cameras and collaborating with local police. Community-led efforts like these underscore the importance of investing in preventative tools and simplifying the legal process.

But real change requires systemic reform. Karachi’s street crime crisis is inseparable from broader failures — a lack of social support, gaping income inequality, and a justice system stretched thin. Without decisive, coordinated action across sectors, residents will continue to live in fear, and the cycle of trauma will persist.

*Names have been changed to ensure privacy and security

Ayesha Mirza is a journalist focusing on social justice, climate change, minority rights and gender issues

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the author