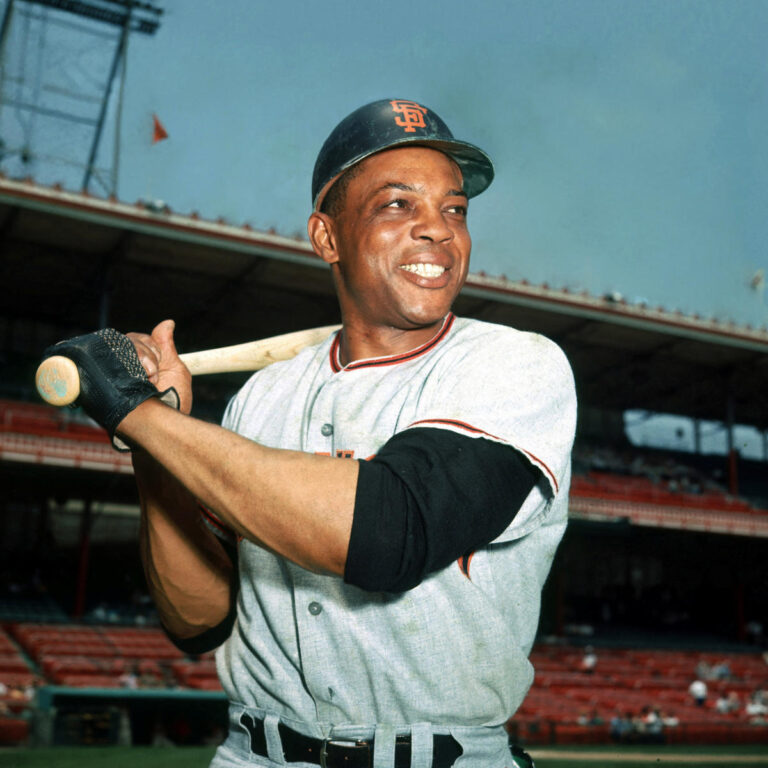

With the passing of Willie Mays on Tuesday, baseball lost a major legend and, to some, the greatest player of all time.

From the objective statistics to the subjective anecdotes, there are endless ways to celebrate Mays’ 23-year major league career. He was the greatest offensive player ever to play center field and produced some of the most iconic defensive highlights. He dominated, he entertained, and he lives on in the memories of all who witnessed his career.

Hits: 3,293. Home runs: 660. All-Star selections: 24. Gold Glove awards: 12. MVP awards: 2 (some say he could have won more). Home run titles: 4. Stolen base titles: 4. A World Series championship, a Rookie of the Year award, a batting title, a four-home run game and the first Roberto Clemente Award for sportsmanship. It’s hard to think of a more perfect resume.

Yet for some reason Mays doesn’t feature as often as others in conversations about the greatest players in baseball history. For a century, the default answer was Babe Ruth. Then Barry Bonds put that conversation on hold for a while, and still does, if you ignore certain shenanigans.

Let’s solve that.

Is Willie Mays the GOAT of MLB?

The argument that there has never been a better baseball player than Mays is certainly valid, especially when you consider some of the complications surrounding how Wins Above Replacement is being used to lead the argument.

First, let’s take a look at Baseball Reference’s all-time WAR rankings.

1. Babe Ruth, 182.6

2. Walter Johnson, 166.9

3. Cy Young, 163.6

4. Barry Bonds, 162.8

5. Willie Mays, 156.2

Have you noticed some of the players ranked higher than Mays?

I don’t need to belabor this, you probably already know how much this statement means to you, but it needs to be said: Willie Mays is the all-time leader in WAR among MLB players who played in integrated leagues and never used steroids.

If Ruth had been born 25 years later and faced the wave of black talent that hit MLB after Jackie Robinson, would he have been as dominant as Mays? We’ll never know. But it’s not hard to make the case that Mays’ time with the Giants was a time when the league’s caliber was at its highest, when every little boy in America wanted to be a baseball player and had the opportunity to do so.

It would be great if that was enough to convince Mays, but it’s entirely possible to support Mays while accepting the premise that Ruth et al. didn’t have an advantage, since the WAR used today is not the same as the WAR used back then, even though they’re treated the same in the record books.

After Willie Mays played, WAR changed how it calculated defense.

Looking back over the decades of MLB history, calculating offensive WAR is relatively easy. Nearly everything at the plate can be boiled down to a few numbers that have survived the transition from literal record books to the online ledgers we use today. Mays hit his home run on May 18, 1957, but we know exactly what impact it had on baseball and how impressive it was, given the pitcher, the ballpark, and the era.

Calculating defensive WAR isn’t that easy because there’s no hard record of how many good catches a player made in his career.

That’s pretty significant considering Baseball Reference projects Mays’ career wins above replacement at 18.2. That ranks him 69th on the all-time Defensive WAR list, which is good but doesn’t really line up with Mays’ defensive reputation. Kevin Kiermaier is a very good defender, but it’s hard to imagine anyone saying he should be more than 10 points above Mays.

For the outfield, modern defensive evaluation essentially involves a human or computer watching the game and recording how far a player had to run to catch the ball (or not catch it). Unfortunately, the system Baseball Reference uses for defensive WAR, Baseball Info Solutions Defensive Runs Saved, only goes back to the 2003 season.

In seasons prior to 2003, Baseball Reference used something called the Total Zone Rating, which didn’t involve tracking players at all. B-Ref says it does the following instead:

Total Zone Rating (TZR) is a non-observational fielding system that relies on a variety of formats based on the level of data available, ranging from basic defensive and pitching statistics to play-by-play including batted ball type and hit location. As much available data is used as possible each season.

When play-by-play is available, TZR uses information such as ground balls caught by infielders and outfielders to estimate the number of hits allowed by infielders, and runners advanced and out information to determine outfielder strength ratings, infielder double play ability and catcher strength ratings.

While the TZR is an impressive feat of statistical engineering, its limitations for our purposes are clear, and are further limited by a lack of play-by-play data for seasons prior to 1953 (Mays debuted in 1951).

The point is, the tool used to evaluate where Mays stands historically relative to other players has some flaws, and normally that’s not a big deal as long as you understand that WAR has a lot of variability (and critics of WAR won’t hesitate to point out when the metric favors players who appear inferior relative to others on other metrics), but it’s an issue here.

But will it be enough to close the 26.4 WAR gap between Mays and Ruth, whose defense is harder to evaluate for the same reasons? Again, it’s hard to say for sure, but it’s definitely worth considering.

Mays is remembered as perhaps the best defensive center fielder of all time, leading his position with 12 Gold Glove awards, but WAR also ranks him as a pretty good defender, and if you don’t think Mays’ defense was better than those numbers would suggest at the time, you clearly haven’t talked to anyone who saw him play in person.

Willie Mays was the greatest hitter-fielder combination of all time.

There are ways to argue against Mays’ dominance, such as the lack of team success given that he only won one (and tainted) World Series. To counter that, swap Mays for Mickey Mantle and see how well the New York Yankees of the 1950s and 60s did. Discussing the MLB GOAT by rings is a pretty silly way to go about it, so I won’t belabor it any more.

Instead, let’s look at Mays in perspective. For two decades, he was one of the league’s most productive and consistent players at the plate, retiring with a 155 OPS+ (meaning, taking into account the ballpark and the era, his OPS was 55% better than league average). At the same time, he was baseball’s best defensive highlight machine. It’s a shame his career took place in an era before highlights were fashionable.

If you’re curious about a player’s highs, Mays eclipsed the historically high 10 WAR in six seasons. If you’re curious about a player’s lows, Mays’ lowest OPS+ from 1954 to 1966 was 146. That year, Mays batted .296, .369, .557 and led the league in stolen bases with 40. If you’re curious about his personality, read all the recollections from people who met him.

When it comes to deciding who the best players in baseball history are, it’s hard not to include Mays on the list, which is why so many people hold him up as the greatest of all time. Personal tastes may vary, but Mays’ career was not one of them.