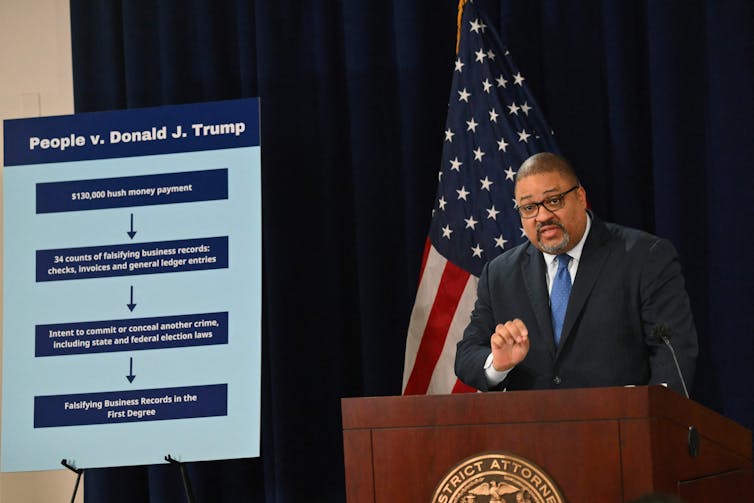

We could debate at length the facts and law behind New York District Attorney Alvin Bragg’s successful prosecution of Donald Trump, but as a government prosecutor for 30 years, I was most concerned with the ethics of prosecuting this case.

“This is a disgrace,” Trump said outside the court after the verdict, echoing comments he has made in the year since he was indicted in the case, in which he has called the prosecutors’ actions “political persecution.”

There is some truth in what he says.

Angela Weiss/AFP via Getty Images

No one has better outlined the important ethical standards that have allowed state and federal prosecutors to maintain an image of honesty and integrity than Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson. In an April 1, 1940, address to federal prosecutors, he said prosecutors should select criminal cases that are “the most egregious and most damaging to the public” and warned that the prosecutor’s power to choose the defendant is “a most dangerous power.”

Selecting defendants requires judgment and that power can be abused, Jackson said.

“The statute books are filled with a wide variety of crimes, so it’s entirely possible that a prosecutor could find a technical violation of some kind of conduct against just about anyone,” Jackson said, adding that in certain cases, “it’s not a matter of finding the fact that a crime was committed and then finding the person who committed that crime, but of identifying the perpetrator and then going through the statute books or getting investigators to commit some kind of crime.”

“The greatest danger of abuse of prosecutorial power occurs when prosecutors pick on people they don’t like or want to embarrass, or pick on unpopular groups, to look for crimes,” Jackson warned.

As a federal prosecutor, I have been proud for many years to stand before a jury and declare, “Ron Siebert represents the United States.” I believed that the majority in the courtroom understood that the federal government has traditionally prosecuted the “most egregious” cases. As Jackson said, these are the cases where the “public harm” is “greatest.”

We prosecutors have maintained a reputation for not prosecuting cases for political reasons by pursuing only cases that have actual victims, in the sense of physical harm or economic loss. The U.S. Department of Justice has an unspoken but long-understood policy that it will never indict or try a politician for a nonviolent crime within one year of an election.

New York’s prosecution of Donald Trump has been, and has been, characterized by some for much longer than today as a “political prosecution” due to the strong belief that a lawsuit based on false records would never have been filed if Trump had not run for president.

Judge Jackson warned that such cases, without an apparent victim, could undermine public perceptions of the prosecution’s legitimacy. The indictment may have angered President Trump, but the real question is whether it undermines the domestic and international integrity that U.S. prosecutors have built up over decades.